Temple of Artemis

The Temple of Artemis (Greek: Ἀρτεμίσιον, or Artemision), also known less precisely as Temple of Diana, was a Greek temple dedicated to a goddess Greeks identified as Artemis that was completed, in its most famous phase, around 550 BC at Ephesus (in present-day Turkey). Though the monument was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, only foundations and sculptural fragments of the temple remain. There were previous temples on its site, where evidence of a sanctuary dates as early as the Bronze Age. The whole temple was made of marble except for the roof.

The temple antedated the Ionic immigration by many years. Callimachus, in his Hymn to Artemis, attributed the origin of the temenos at Ephesus to the Amazons, whose worship he imagines already centered upon an image. In the seventh century the old temple was destroyed by a flood. The construction of the "new" temple, which was to become known as one of the wonders of the ancient world, began around 550 BC. It was a 120-year project, initially designed and built by the Cretan architect Chersiphron and his son Metagenes, at the expense of Croesus of Lydia.

It was described by Antipater of Sidon, who compiled the list of the Seven Wonders:

I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the hanging gardens, and the colossus of the Sun, and the huge labour of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus; but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, "Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand".[1]

Contents |

Location

The Temple of Artemis was located near the ancient city of Ephesus, about 50 km south from the modern port city of İzmir, in Turkey. Today the site lies on the edge of the modern town of Selçuk.

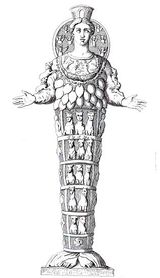

Ephesian Artemis

Artemis was a Greek Goddess, the virginal huntress and twin of Apollo, who supplanted the Titan Selene as goddess of the Moon. Of the Olympian goddesses who inherited aspects of the Great Goddess of Crete, Athena was more honored than Artemis at Athens. At Ephesus, a goddess whom the Greeks associated with Artemis was passionately venerated in an archaic, certainly pre-Hellenic cult image[2] that was carved of wood and kept decorated with jewelry. Robert Fleischer identified as decorations of the primitive xoanon the changeable features that since Minucius Felix and Jerome's Christian attacks on pagan popular religion had been read as many breasts or "eggs" — denoting her fertility (others interpret the objects to represent the testicles of sacrificed bulls that would have been strung on the image, with similar meaning). Most similar to Near-Eastern and Egyptian deities, and least similar to Greek ones, her body and legs are enclosed within a tapering pillar-like term, from which her feet protrude. On the coins minted at Ephesus, the apparently many-breasted goddess wears a mural crown (like a city's walls), an attribute of Cybele (see polos). On the coins she rests either arm on a staff formed of entwined serpents or of a stack of ouroboroi, the eternal serpent with its tail in its mouth. Something the Lady of Ephesus had in common with Cybele was that each was served by temple slave-women, or hierodules (hiero "holy", doule "female slave"), under the direction of a priestess who inherited her role, attended by a college of eunuch priests called "Megabyzoi"[3] and also by young virgins (korai).[4]

The "eggs" or "breasts" of the Lady of Ephesus, it now appears, must be the iconographic descendents of the amber gourd-shaped drops, elliptical in cross-section and drilled for hanging, that were rediscovered in 1987-88; they remained in situ where the ancient wooden cult figure of the Lady of Ephesus had been caught by an eighth-century flood (see History below). This form of breast-jewelry, then, had already been developed by the Geometric Period. A hypothesis offered by Gerard Seiterle, that the objects in Classical representations represented bulls' scrotal sacs[5] cannot be maintained.[6]

A votive inscription mentioned by Florence Mary Bennett,[7] which dates probably from about the third century BC, associates Ephesian Artemis with Crete: "To the Healer of diseases, to Apollo, Giver of Light to mortals, Eutyches has set up in votive offering [a statue of] the Cretan Lady of Ephesus, the Light-Bearer."

The Greek habits of syncretism assimilated all foreign gods under some form of the Olympian pantheon familiar to them— in interpretatio graeca— and it is clear that at Ephesus, the identification with Artemis that the Ionian settlers made of the "Lady of Ephesus" was slender. The Christian approach was at variance with the tolerant syncretistic approach of pagans to gods who were not theirs. A Christian inscription at Ephesus[8] suggests why so little remains at the site:

"Destroying the delusive image of the demon Artemis, Demeas has erected this symbol of Truth, the God that drives away idols, and the Cross of priests, deathless and victorious sign of Christ."

The assertion that the Ephesians thought that their cult image had fallen from the sky, though it was a familiar origin-myth at other sites, is only known at Ephesus from Acts 19:35:

"What man is there that knoweth not how that the city of the Ephesians is a worshipper of the great goddess Diana, and of the [image] which fell down from Jupiter?"

Lynn LiDonnici observes that modern scholars are likely to be more concerned with origins of the Lady of Ephesus and her iconology than her adherents were at any point in time, and are prone to creating a synthetic account of the Lady of Ephesus by drawing together documentation that ranges over more than a millennium in its origins, creating a falsified, unitary picture, as of an unchanging icon.[9]

History

The sacred site at Ephesus was far older than the Artemision. Pausanias[10] understood the shrine of Artemis there to be very ancient. He states with certainty that it antedated the Ionic immigration by many years, being older even than the oracular shrine of Apollo at Didyma. He said that the pre-Ionic inhabitants of the city were Leleges and Lydians. Callimachus, in his Hymn to Artemis, attributed the origin of the temenos at Ephesus to the Amazons, whose worship he imagines already centered upon an image (bretas).

Pre-World War I excavations by David George Hogarth,[11] who identified three successive temples overlying one another on the site, and corrective re-excavations in 1987-88[12] have confirmed Pausanias' report.

Test holes have confirmed that the site was occupied as early as the Bronze Age, with a sequence of pottery finds that extend forward to Middle Geometric times, when the clay-floored peripteral temple was constructed, in the second half of the eighth century BC.[13] The peripteral temple at Ephesus was the earliest example of a peripteral type on the coast of Asia Minor, and perhaps the earliest Greek temple surrounded by colonnades anywhere.

In the seventh century, a flood[14] destroyed the temple, depositing over half a meter of sand and scattering flotsam over the former floor of hard-packed clay. In the flood debris were the remains of a carved ivory plaque of a griffin and the Tree of Life, apparently North Syrian. More importantly, flood deposits buried in place a hoard against the north wall that included drilled amber tear-shaped drops with elliptical cross-sections, which had once dressed the wooden effigy of the Lady of Ephesus; the xoanon itself must have been destroyed in the flood. Bammer notes that though the flood-prone site was raised by silt deposits about two metres between the eighth and sixth centuries, and a further 2.4 m between the sixth and the fourth, the site was retained: "this indicates that maintaining the identity of the actual location played an important role in the sacred organization" (Bammer 1990:144).

The new temple, now built of marble, with its peripteral columns doubled to make a wide ceremonial passage round the cella, was designed and constructed around 550 BC by the Cretan architect Chersiphron and his son Metagenes. A new ebony or grapewood cult statue was sculpted by Endoios,[15] and a naiskos to house it was erected east of the open-air altar.

This enriched reconstruction was built at the expense of Croesus, the wealthy king of Lydia.[16] The rich foundation deposit of more than a thousand items has been recovered: it includes what may be the earliest coins of the silver-gold alloy electrum. Fragments of the bas-reliefs on the lowest drums of Croesus' temple, preserved in the British Museum, show that the enriched columns of the later temple, of which a few survive (illustration, below right) were versions of the earlier feature. Marshy ground was selected for the building site as a precaution against future earthquakes, according to Pliny the Elder.[17] The temple became a tourist attraction, visited by merchants, kings, and sightseers, many of whom paid homage to Artemis in the form of jewelry and various goods. Its splendor also attracted many worshipers.

Croesus' temple was a widely respected place of refuge, a tradition that was linked in myth with the Amazons who took refuge there, both from Heracles and from Dionysus.

Destruction

The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus was destroyed on July 21, 356 BC in an act of arson committed by Herostratus. According to the story, his motivation was fame at any cost, thus the term herostratic fame.

A man was found to plan the burning of the temple of Ephesian Diana so that through the destruction of this most beautiful building his name might be spread through the whole world.[18]

The Ephesians, outraged, sentenced Herostratus to death and forbade anyone from mentioning his name, with the penalty for doing so being death.Theopompus later noted the name, which is how it is known today.[19]

That very same night, Alexander the Great was born. Plutarch remarked that Artemis was too preoccupied with Alexander's delivery to save her burning temple. Alexander later offered to pay for the temple's rebuilding, but the Ephesians refused. Eventually, the temple was restored after Alexander's death, in 323 BC.

This reconstruction was itself destroyed during a raid by the Goths, an East Germanic tribe, in 268,[20] in the time of emperor Gallienus: "Respa, Veduc and Thuruar,[21] leaders of the Goths, took ship and sailed across the strait of the Hellespont to Asia. There they laid waste many populous cities and set fire to the renowned temple of Diana at Ephesus," reported Jordanes in Getica.[22]

The Ephesians rebuilt the temple again. The temple appears multiple times in Christian accounts of Ephesus. According to the New Testament, the appearance of the first Christian missionary in Ephesus caused locals to fear for the temple's dishonor.[23] The Ephesians rebuilt the temple again. The temple appears multiple times in Christian accounts of Ephesus. The second-century Acts of John includes a story of the temple's destruction: the apostle John prayed publicly in the very Temple of Artemis, exorcising its demons and "of a sudden the altar of Artemis split in many pieces... and half the temple fell down," instantly converting the Ephesians, who wept, prayed or took flight.[24] Over the course of the fourth century, perhaps the majority of Ephesians did convert to Christianity; all temples were declared closed by Theodosius I in 391.

In 401, the temple in its last version was finally destroyed by a mob led by St. John Chrysostom,[25] and the stones were used in construction of other buildings. Some of the columns in Hagia Sophia originally belonged to the temple of Artemis,[26] and the Parastaseis syntomoi chronikai records the re-use of several statues and other decorative elements throughout Constantinople.

The main primary sources for the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus are Pliny the Elder's Natural History XXXVI.xxi.95, Pomponius Mela i:17, and Plutarch's Life of Alexander III.5 (referencing the burning of the Artemiseum).

Rediscovery

After sixty years of searching, the site of the temple was rediscovered in 1869 by an expedition sponsored by the British Museum led by John Turtle Wood;[27] excavations continued until 1874.[28] A few further fragments of sculpture were found during the 1904-06 excavations directed by David George Hogarth. The recovered sculptured fragments of the fourth-century rebuilding and a few from the earlier temple, which had been used in the rubble fill for the rebuilding, were assembled and displayed in the "Ephesus Room" of the British Museum.[29]

Today the site of the temple, which lies just outside Selçuk, is marked by a single column constructed of dissociated fragments discovered on the site.

Architecture and art

Most of the physical description and art within the Temple of Artemis comes from Pliny, though there are different accounts, and the actual size varies.

Pliny describes the temple as 377 feet (115 meters) long and 180 feet (55 meters) wide, made almost entirely of marble, making its area about three times as large as the Parthenon. The temple's cella was enclosed in colonnades of 127 Ionic columns, each 60 feet (18 meters) in height.

The Temple of Artemis housed many fine works of art. Sculptures by renowned Greek sculptors Polyclitus, Pheidias, Cresilas, and Phradmon adorned the temple, as well as paintings and gilded columns of gold and silver. The sculptors often competed at creating the finest sculpture. Many of these sculptures were of Amazons, who were said to have founded the city of Ephesus.

Pliny tells us that Scopas, who also worked on the Mausoleum of Mausollos, worked carved reliefs into the temple's columns. Athenagoras of Athens names Endoeus, a pupil of Daedalus, as the sculptor of the main statue of Artemis in Ephesus.

Cult and influence

The Temple of Artemis was located at an economically robust region, drawing merchants and travellers from all over Asia Minor. The temple was influenced by many beliefs, and can be seen as a symbol of faith for many different peoples. The site also drew pilgrims, peasants, and artisans. The Ephesians worshiped Cybele, and incorporated many of their beliefs into the worship of Artemis. Artemisian Cybele became quite contrasted from her Roman counterpart, Diana. The cult of Artemis attracted thousands of worshippers from far-off lands.

See also

- Ephesia Grammata

- Temple of Diana

- Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

References

Notes

- ↑ Antipater, Greek Anthology IX.58.

- ↑ The iconic images have been most thoroughly assembled by Robert Fleischer, Artemis von Ephesos und der erwandte Kultstatue von Anatolien und Syrien EPRO 35 (Leiden:Brill) 1973.

- ↑ Strabo, Geographica, 14.1.23<; sometimes the existence of a college is disputed and rather, a succession of priests given the title of "Megabyzos" is preferred.

- ↑ Xenophon, Anabasis, v.3.7.

- ↑ Seiterle, "Artemis: die Grosse Göttin von Ephesos" Antike Welt 10 (1979), pp 3-16, accepted in the 1980s by Walter Burkert and Brita Alroth, among others, criticised and rejected by Robert Fleischer, but widely popularized.

- ↑ Fleischer, "Neues zur kleinasiatischen Kultstatue" Archäologischer Anzeiger 98 1983:81-93; Bammer 1990:153.

- ↑ Florence Mary Bennett, Religious Cults Associated with the Amazons (1912): Chapter III: Ephesian Artemis (on-line text).

- ↑ Quoted in Ramsay MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire AD 100-400 1984, ch. III "Christianity as presented" p. 18.

- ↑ Lynn R. LiDonnici, "The Images of Artemis Ephesia and Greco-Roman Worship: A Reconsideration" The Harvard Theological Review 85.4 (October 1992), pp 389-415.

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece 7.2.6.

- ↑ D.G. Hogarth, editor, 1908. Excavations at Ephesus.

- ↑ Anton Bammer, "A Peripteros" of the Geometric Period in the Artemision of Ephesus" Anatolian Studies 40 (1990), pp. 137-160

- ↑ Bammer (1990:142) noted some still earlier placements of stones, Mycenaean pottery and crude clay animal figurines, but warned "it is still to early to come to conclusions about a cult sequence."

- ↑ The flood is dated by fragmentary ceramics. (Bammer 1990:141).

- ↑ Pliny's Natural History, 16.79.213-16; Pliny's source was the Roman Mucianus, who thought that the cult image by an "Endoios" was extremely ancient, however. Endoios' name appears in late sixth-century Attic inscriptions; work attributed to him was noted by Pausanias. The more important fact, as Lynn LiDonnici points out, is that Ephesians remembered that a particular sculptor had created the remade image (LiDonnici 1992:398.)

- ↑ Herodotus' statement to this effect is confirmed by the conjectural reading of a fragmentary dedicatory inscription, conserved in the British Museum (A Guide to the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities in the British Museum 84).

- ↑ Pliny's rationalized narrative of site selection did not take into account the antiquity of the sacred site.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus, VIII.14.ext.5

- ↑ Smith, William (1849). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. pp. 439. http://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-bio/1547.html. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ↑ 268: Herwig Wolfram, Thomas J. Dunlap, tr., History of the Goths (1979) 1988:52f, correlating multiple sources, corrects the date of the Gothic advance into the Aegean against the Origo Gothica, which scrambles the events of several years, giving 267 for this event.

- ↑ Respa, Veduco, Thurar: these names are otherwise unknown (Wolfram 1988:52 and note 84).

- ↑ Jordanes, Getica xx.107.

- ↑ Acts 19:27

- ↑ Ramsay MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire A.D. 100-400 1984, p 26.

- ↑ John Freely, The Western Shores of Turkey: Discovering the Aegean and Mediterranean Coasts 2004, p. 148

- ↑ St. Sophia Construction for the Third Time

- ↑ J.T. Wood

- ↑ "Ephesos - An Ancient Metropolis: Exploration and History". Austrian Archaeological Institute. October 2008. http://www.oeai.at/eng/ausland/geschichte.html. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ The sculptures were published in the British Museum Catalogue of Sculpture, vol. II, part VI.

Bibliography

- Anton Bammer, "A Peripteros" of the Geometric Period in the Artemision of Ephesus" Anatolian Studies 40 (1990), pp. 137–160.

- Lynn R. LiDonnici, "The Images of Artemis Ephesia and Greco-Roman Worship: A Reconsideration" The Harvard Theological Review 85.4 (October 1992), pp 389–415.

External links

- Temple of Artemis (Ephesos) objects at the British Museum website

- Florence Mary Bennett, Religious Cults Associated with the Amazons: (1912): Chapter III: Ephesian Artemis (text)

- James Grout: Temple of Artemis, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Diana's Temple at Ephesus (W. R. Lethaby, 1908)

|

|||||